Boston: He illustrated Civil War reconciliation. What would he draw today?

What would it take for us to imagine political harmony?

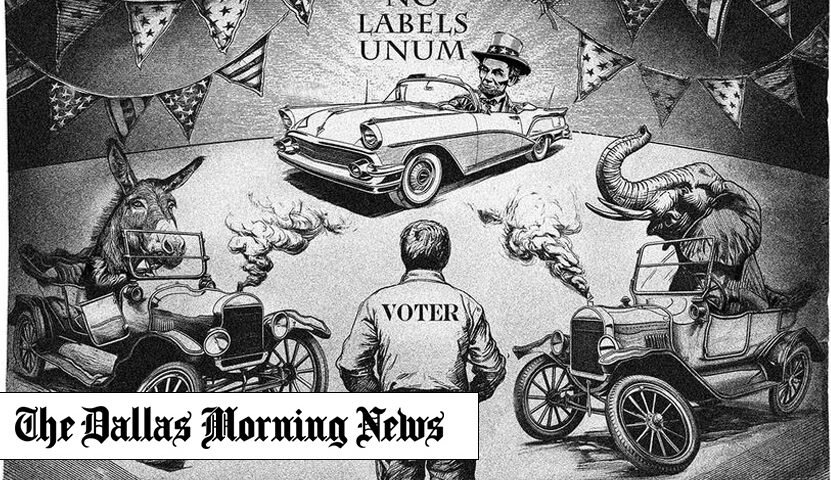

Thomas Nast illustrated reconciliation after the Civil War. Through the talented pencil of staff illustrator Michael Hogue, contributing columnist Talmage Boston imagines how he might illustrate America’s divided political situation today.(Michael Hogue)With the election eight months away, and contempt between adversaries locked in, millions have now chosen to reject the Founding Fathers’ goal of e pluribus unum and, with it, the ideal that we should do what it takes to pursue unity amid conflicting factions.

So what would it take? To answer that question, a picture may be worth a thousand words.

Thomas Nast, whose work appeared in Harper’s Weekly from 1859 to 1886, has been called the “father of the American cartoon.” He elevated the nation’s hopes for the future during that time of heightened division. In his stellar biography, Abe, David S. Reynolds quotes President Abraham Lincoln on Nast’s importance to the Union during the Civil War: “He’s been our best recruiting sergeant. His emblematic cartoons have never failed to arouse enthusiasm and patriotism, and always came when those articles were getting scarce.”

The division in Nast’s day makes today’s political skirmishing look like a sandbox quarrel. Yet Nast’s Dec. 31, 1864, cartoon, The Union Christmas Dinner, showed what America’s mindset needed to be if the nation sought to achieve a successful integration of the Confederate states back into the Union when the war ended.

Lincoln had been reelected in November 1864, Sherman captured Savannah, Ga., in December, and Union victory under Grant’s field leadership appeared inevitable. The president’s address to Congress on December 6 established the terms he’d accept to end the war and how he planned to push through the Thirteenth Amendment to abolish slavery. His speech to Congress made clear that his approach for reconnecting with Southerners would be through a policy of “open door” reconciliation.

Nast met with Lincoln six days after that speech. There’s no record of what they discussed, but it’s not hard to speculate, given what the president said before and after their meeting, and what the artist created in his masterpiece.

Lincoln may have shared with Nast how best to start bridging the nation’s divide based on what he’d learned from studying the life of his hero, Thomas Jefferson, who, 63 years before, had set the standard for promoting e pluribus unum.

The Sedition Act had been passed by the Federalist-controlled Congress in 1798 during John Adams’ presidency, and made it a crime punishable by incarceration for anyone to criticize Adams and Federalist policies. Thankfully for the country, the flagrantly unconstitutional law expired when Adams’ term ended. In hopes of restoring unity, Jefferson, Adams’ successor, proclaimed in his March 4, 1801, inaugural address, “We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.”

In other words, “We are all Americans! And we better start acting that way if we want our new nation to survive.”

Acting on his message, the charming Jefferson hosted small dinners every week of his presidency where he entertained leading Republicans and Federalists. In his Jefferson biography, Jon Meacham concluded that the meals made animosity lessen because the president’s “social civility, grace and hospitality softened the strident hours of partisanship … and feelings evolved from hostility to at least partial respect.”

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/dmn/45QYXR3LAFFZBG6CAUQLHMUAXE.jpg)

Mirroring Jefferson’s approach in The Union Christmas Dinner, Nast depicted Lincoln opening the door to welcome Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Gen. Robert E. Lee and Southern governors to a Christmas feast attended by Northern governors already seated at a table with portraits of Union generals hanging on the wall.

Surrounding this welcoming dinner image were five smaller drawings that enhanced the theme of reconciliation: an olive branch offered by the victor to the defeated; a loving father embracing his returning prodigal son; the necessary unconditional surrender by Lee to Grant to end the war; Union soldiers ready to embrace their Southern counterparts once they laid down their arms; and the joyful festivities that would take place when peace arrived.

As Nast wove these images into his (and Lincoln’s) message of postwar reconciliation, he may have been influenced by the theme Lincoln put into words during his second inaugural address, given three months later. Perhaps Lincoln even shared them with Nast. They could have easily served as the pre-meal blessing to any banquet Lincoln hosted:

Both [North and South] read the same Bible and pray to the same God. … Let us judge not, that we be not judged … The Almighty has his own purposes. … With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in. … to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

Amazingly, as the Civil War came to an end, it was perceived as an achievable goal from Lincoln’s and Nast’s perspective for men to forgive, socialize and rebuild relationships with those who had recently been responsible for killing their loved ones.

That was then; but what about now? Knowing the state of today’s political sentiments, if he were alive today, would Nast portray the same hopeful spirit of reconciliation between, for example, those who stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, and those outraged by that insurrection? Or, in fact, does the goal of inspiring a spirit of unity and reconciliation in 2024′s poisonous political climate only prompt idle thoughts of Don Quixote tilting at windmills? If Thomas Nast were still around, what would he draw in 2024 in an attempt to convey a sense of hope for the future?

I think Nast might create an image along the following lines: A person in the market for a car (labeled “Voter”) sees to his right an old, broken-down Ford with an incapacitated person in the driver’s seat (labeled “Republican”), and to his left an old, broken-down Chevy with an incapacitated person in the driver’s seat (labeled “Democrat”). On either side of the prospective buyer are salesmen pressuring him to think that Ford or Chevrolet are the only vehicle options he has. On the horizon, however, is a different model car (labeled “No Labels Unum”) that’s operational and ready to go.

Nast might find the alternative transportation option appealing since he knew that today’s Republican Party started out as an alternative third party in 1854. The time was right then for something new and hopefully better than the series of ineffective presidents Democrats and Whigs had been offering. That third party brought Abraham Lincoln to the forefront, who turned out to be the candidate most capable of leading the nation through the Civil War because he always channeled the better angels of our nature and took personal responsibility for bringing e pluribus unum back to the nation’s mindset, until sadly an assassin’s bullet ended his life.

Having remembered the ultimate success of the third party in 1854, to put the finishing touches on his new drawing, Nast might sketch a figure in the Unum vehicle’s driver’s seat with the profile of an Abraham Lincoln/Uncle Sam hybrid. Last but not least, in 2024, he would write the cartoon’s title at the bottom of the page: May History Repeat Itself.