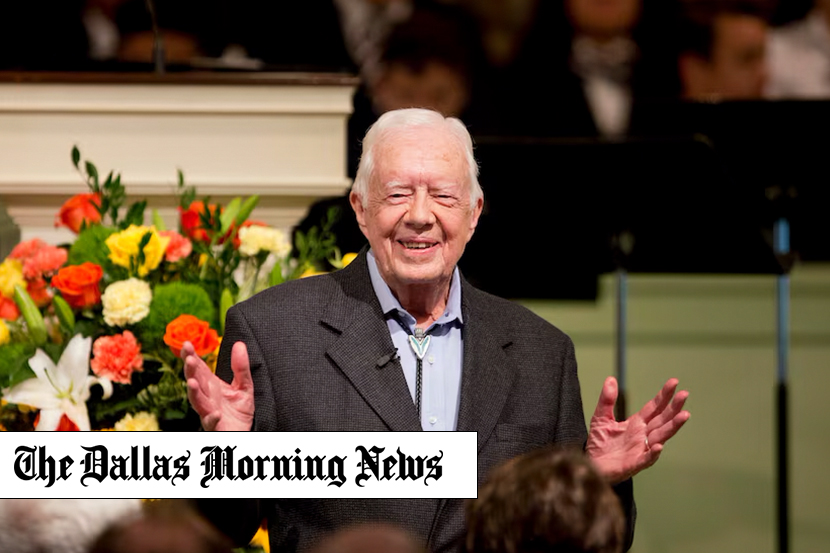

Former President Jimmy Carter teaches a Sunday school class at the Maranatha Baptist Church in his hometown of Plains, Ga., on Aug. 23, 2015. His was a long life well lived as a naval nuclear engineer, farmer, governor, president, mediator, husband, father, grandfather, best-selling author, Habitat for Humanity carpenter and Sunday school teacher, Talmage Boston writes.(David Goldman / AP)

Jimmy Carter’s most enduring lesson

His legacy is how much can be accomplished when smart leaders cast aside all notions of hostile partisanship.

Passing away shortly after his 100th birthday, having lived longer than any other president, deeply religious Jimmy Carter has presumably now entered the Pearly Gates to meet his maker.

My hunch is that our Heavenly Father’s first question of his new resident is not, “Jimmy, from January 1977 to January 1981, how effective were you during your White House years?” I suspect that instead, his query is more like, “Jimmy, from October 1924 to December 2024, did you lead a life marked by good deeds and steadfast integrity?”

Harry Truman said of the time needed to make sound historical assessments, “It takes 50 years for the dust to settle.” Forty-two years after leaving the Oval Office, Jimmy Carter is rated by America’s leading historians in the most recent (2021) C-SPAN presidential ranking poll as our 26th best commander-in-chief, which means he’s not in the top half. In C-SPAN’s most recent polls (2000, 2009, 2017, and 2021), he’s received low scores in the presidential command traits of public persuasion, crisis leadership, economic management, administrative skills, relations with Congress and performance in the context of the times, though he’s gotten high marks in moral authority and the pursuit of equal justice. Such evaluations of Carter’s four years at the helm by those most knowledgeable in presidential history appear to align with the consensus view of non-scholars.

On the occasion of his death, however, after a long life well lived as a naval nuclear engineer, farmer, governor, president, mediator, husband, father, grandfather, best-selling author, Habitat for Humanity carpenter and Sunday school teacher, one story about Jimmy Carter seems especially instructive as the nation heads toward next year’s inauguration and its anticipated extreme level of political discord. I learned of it in Nancy Gibbs and Michael Duffy’s terrific book, The Presidents Club: Inside the World’s Most Exclusive Fraternity (Simon & Schuster 2012).

The time was October 1981, and President Ronald Reagan was still recovering from his almost fatal encounter with an assassin’s bullet. Egyptian President Anwar Sadat had just been killed, and Reagan was not healthy enough to travel halfway around the world to attend the funeral and was reluctant to send Vice President George H.W. Bush. Thus, he asked his White House predecessors Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter to take his place at Sadat’s service.

During the long flight to Cairo on Air Force One, tension filled the plane because of the past presidents’ strained relations caused by Ford’s having pardoned Nixon shortly after his resignation in the summer of 1974, which Carter used as his major campaign issue to defeat Ford in 1976’s down-to-the-wire election. Gibbs and Duffy reported that as the group crossed the Atlantic, “Ford and Carter seemed determined not to get along. Their wounds were deeper, their anger fresher. ‘Oil and water,’ Carter explained early in the flight. ‘They had no use for each other,’ said a Ford aide later.”

Following Sadat’s funeral, Ford and Carter spent several hours together on their return to the United States, since Nixon had stayed behind for some type of mysterious meeting. Their flight proximity began with a joint interview conducted by the press on the plane, and in it, the two former presidents gave surprisingly shared views on how best to handle the Middle East. Then something magical happened. Wrote Gibbs and Duffy: “Their conversation quickly turned more casual and everyone noticed that the presidents were virtually finishing each other’s sentences, using their first names, and going out of their way to praise each other on various issues.”

After the interview ended, the former antagonists kept sitting together, talking, and comparing notes on the difficulty of fundraising for their respective presidential libraries. Ford said later, “We found we had a lot of things in common.”

When the unexpectedly harmonious flight ended, the two men committed to form a “presidents club” partnership, and over the next 26 years, they continued to bond, teamed up on dozens of worthwhile projects, lobbied foreign policy issues together, and even made an agreement that when the first of them died, the survivor would deliver the eulogy at the decedent’s funeral.

On Jan. 2, 2007, during Gerald Ford’s memorial service at Grace Episcopal Church in Grand Rapids, Mich., Jimmy Carter said these words:

“For myself and for our nation, I want to thank my predecessor for all he has done to heal our land.” These were the first words I spoke as president. And I still hate to admit that they received more applause than any other words in my inaugural address. … You learn a lot about a man when you run against him for president, and when you stand in his shoes, and assume the responsibilities he has borne so well, and perhaps even more after you both lay down the burdens of high office and work together in a non-partisan spirit of patriotism and service. … Jerry and I frequently agreed that one of the greatest blessings we had after we left the White House during the last quarter century was the intense personal friendship that bound us together.”

Jimmy Carter’s greatest legacy may well be to show us how much good can be accomplished when smart, high-integrity political leaders cast aside all notions of hostile partisanship, lock arms in a spirit of service to a higher calling, and work together to make the world a better place.