Published May 3rd, 2024

It’s been said that those who don’t learn history are doomed to repeat it.

That’s good counsel when it comes to avoiding costly mistakes. But what about history lessons that underscore positive behaviors and achievements worthy of emulation?

Talmage Boston answers that question in How the Best Did It: Leadership Lessons from Our Top Presidents.

Boston, a partner in a Dallas law firm, has written several history books with forewords by the likes of John Grisham and Ken Burns, and endorsements by acclaimed historians like David McCullough and Jon Meacham.

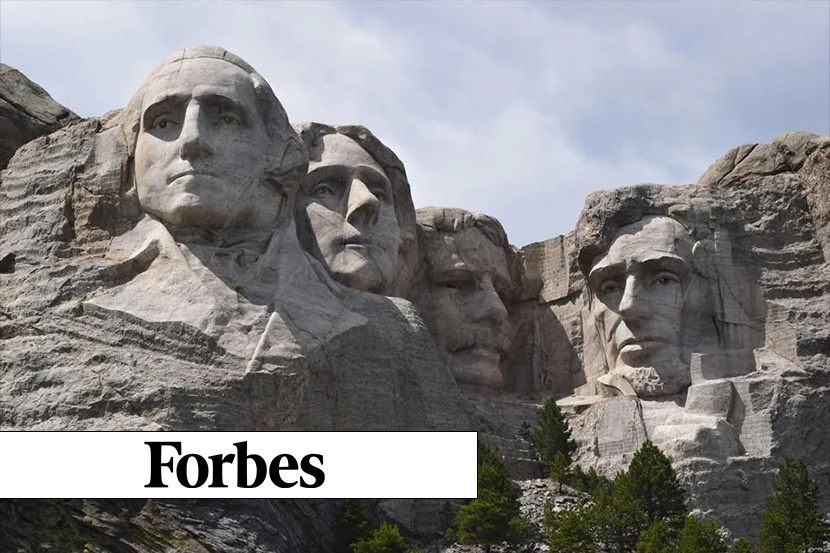

In his latest book, Boston focuses on eight U.S. presidents: Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, Kennedy, Eisenhower, Reagan, and both Roosevelts.

Why should we rely on historical assessments made by someone whose career vocation has been as a litigator and writes about history only as an avocation?

Each chapter on a president in Boston’s book was reviewed, tweaked, and ultimately approved by at least two major biographers of that president. His conclusions about the most important leadership traits of the eight presidents have been vetted by prominent presidential historians, including three Pulitzer Prize winners.

Let’s dive in with some questions.

Many people would like to move up in their company ranks but want to avoid coming across as self-promoters. What can they learn from George Washington?

“Washington was a man who accomplished important deeds,” Boston says. “By leading the overmatched Continental Army to victory in the Revolutionary War and then presiding over the successful Constitutional Convention, his achievements earned him the universal respect of America’s top political leaders. Thus, he didn’t need to promote himself, because his nation-changing deeds spoke for themselves and led to his being unanimously chosen as our first president.”

Boston says Washington epitomized command presence. “He was always the tallest guy in the room,” he says. “He carried himself with perfect posture. He wore immaculate attire. He listened attentively while maintaining piercing eye contact. He demonstrated athletic grace in his movements. He was always mounted on a white horse. And he stayed in a mode of steadfast intelligence by insisting on knowing all sides of an issue before making final decisions. In addition to all that, he had unwavering integrity, and thus had total credibility which, when combined with (a) and (b), consistently earned him the trust of others.”

Some organizations are dysfunctional because of internal conflicts that produce gridlock and petty one-upmanship. How can lessons from Thomas Jefferson be applied to such a scenario?

Boston says that in his relentless relationship-building efforts at the dinners with political friends and foes that he hosted two or three times a week throughout his presidency, Jefferson broke down partisan walls by acting in alignment with two timeless interrelated adages:

Politics is all about relationships. “It’s hard to get people to go your way when you’re a stranger or mere acquaintance,” Boston says. “Followers typically embrace leaders they know well, like, and trust. And those objectives are most likely to be fulfilled in the context of having a deep positive relationship.”

If someone likes you, he’ll give you the benefit of the doubt. “So many controversial political issues have sound arguments that support the conflicting positions,” Boston says. “The side that ultimately prevails is usually the one approved by those with the most influence. The more people know and respect you, the more likely they are to support your position in a close call situation.”

Incivility and outright hostility seem to be rampant in our society. How could Abraham Lincoln’s example of taking the high road be useful in dealing with such an environment?

“Many times throughout his presidency, Lincoln received insults and incivility from his ‘team of rivals’ Cabinet members, Union generals, anti-war Democratic Party ‘Copperhead’ leaders, and even his wife Mary,” Boston says. “His self-disciplined position in resisting all of the undermining efforts that came at him from those people was, ‘I won’t take the bait.’ He understood that getting bogged down in interpersonal strife would make him take his eyes off his three targets: Win the Civil War. Abolish slavery. Reunite the nation. So, if a leader wants to achieve his highest goals, he’s more likely to succeed if he stays away from petty turf battles and maintains his position above the fray.”

It’s not unusual for people to be confronted by unforeseen obstacles that might seem insurmountable. What can they learn from Franklin D. Roosevelt?

“FDR’s finding a way to rebuild his life and ultimately prevail over polio is one of the most inspiring stories in American history,” Boston says. “Before contracting the virus at age 39, he was physically active and socially dynamic. With polio, his prior lifestyle ended in a flash because one morning he woke up and his legs had stopped working. It took him seven years to get back into the stream of life and climb again to the highest level of politics.’

In the 24 years he had polio, Boston says, FDR never sought sympathy and did everything he could to hide his disability. “In her husband’s response to the setback, Eleanor Roosevelt noticed that he became less arrogant and more empathetic and patient with others, and that personality transformation greatly enhanced his political appeal,” Boston says. “His heroic response to polio led to major self-improvement that was an important factor in his winning four presidential elections by overwhelming margins. The lemonade he made from the polio lemon is a lesson for all of us in how best to handle adversity.”

.

.

John F. Kennedy had a number of high-strung, head-strong people in his inner circle of advisers. What can we learn from his decision-making during the Cuban missile crisis?

“Three months into his presidency, JFK learned from the Bay of Pigs fiasco in April 1961 that to rely on the advice of so-called experts without engaging in his own independent evaluation of what they recommended was a recipe for disaster,” Boston says. “By the time the Cuban Missile Crisis arose in October 1962, he took advice from his Executive Committee and Joint Chiefs of Staff with a boxful of salt grains. During the crisis, he considered all options on how best to deal with Khrushchev and the Soviet missiles, and then chose his own naval blockade and negotiation strategy that produced the favorable result. The 42 hours of tape recordings from the meetings with his advisors during the 13 days demonstrate that at all times Kennedy had the clearest head and calmest spirit in the room as he confronted and ultimately avoided the real threat of a nuclear holocaust.”

Ronald Reagan had many critics, especially in the media. But, as Boston points out, he “maintained a strong, steady, and eloquent approach to bringing down the Soviet totalitarian regime” to end the Cold War without firing a shot. What can today’s leaders (political and otherwise) learn from that example?

“Reagan’s successful foreign policy aimed at winning the Cold War was the result of his unwavering optimism and unyielding follow-through on his long-term vision,” Boston says. “From the outset of his political career, he knew he wanted to defeat the communist Soviet Union, and he steadily moved in the direction of achieving that goal until the world-changing opportunity materialized when the Soviet economy started to fail, and Mikhail Gorbachev became the first ever conciliatory General Secretary of the Communist Party.”

Boston recommends five “personal application” questions for people who seriously strive to be effective leaders:

- How much do you listen compared to how much do you talk? (Washington

- Do you deliberately schedule times to think in solitude? (Jefferson).

- What is your level of due diligence before you make a promise? (Lincoln).

- When people are at loggerheads in your organization, do you intervene promptly and act as a mediator? (Theodore Roosevelt).

- Do you speak to your work colleagues about the major issues facing your organization too often, too rarely, or just the right frequency? (Franklin Roosevelt).

Boston says the benefits should be evident if readers simply take the time to pause, reflect, and answer these questions honestly.

Click here to read full article.