JFK: 60 years after his short and extraordinary presidency

Too much has been written about his death and personal life, not enough about his legacy.

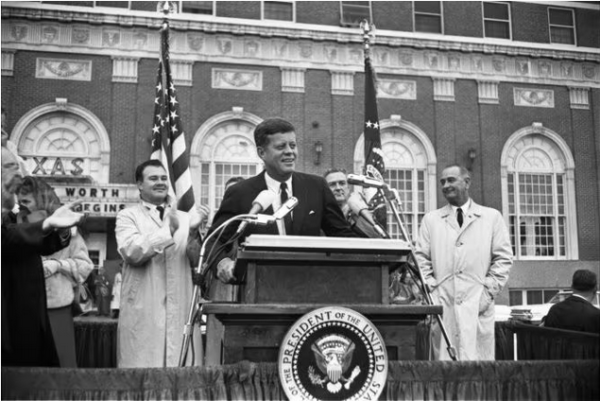

In this Nov. 22, 1963, photo provided by the The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza, John F. Kennedy speaks outside the Hotel Texas in Fort Worth. When Kennedy took office he soon realized he had much to learn. So he pursued crash courses in foreign and economic policy, and never stopped improving in those critical areas until the day he died, writes Talmage Boston.

It’s been six decades since John F. Kennedy was killed in our city. Nov. 22, 1963, is “a day which will live in infamy,” to borrow a phrase from another president about another awful day.

In the opinion of this scrivener, over the last 60 years, too much attention has been paid to JFK’s assassination and his unflattering personal life, and not enough to his extraordinary presidency. Harry Truman said “it takes 50 years for the dust to settle” on evaluating historical figures. This anniversary of Kennedy’s death is a good time to assess his White House years.

In 2017 and 2021, America’s leading historians cast their most recent votes in C-SPAN’s presidential rankings polls. Both times they rated JFK as our eighth greatest president, behind only Lincoln, Washington, both Roosevelts, Eisenhower, Truman and Jefferson. Kennedy received this grade despite having the seventh shortest stint at the helm. Joe Biden has now served in the Oval Office longer than John Kennedy.

Opinion

Get smart opinions on the topics North Texans care about.

What supports his high ranking? In my upcoming book, How the Best Did It: Leadership Lessons From Our Top Presidents, I explain how the success of Kennedy’s concentrated presidency came through three leadership traits.

First, he was a quick study. He took office at age 43 and soon realized he had much to learn. So he pursued crash courses in foreign and economic policy and never stopped improving in those critical areas until the day he died.

Foreign policy

Kennedy made the overreaching promise in his inaugural address to “pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, and oppose any foe to assure the survival and success of liberty” around the world. Three months later, per that promise, he approved the CIA’s plan to overthrow Fidel Castro in an invasion at the Bay of Pigs. It became a humiliating fiasco when Castro’s troops defeated the attack in a nanosecond.

In his JFK biography, Hugh Sidey concluded that the early ill-fated decision about Cuba “activated the chemistry of the Kennedy soul, which developed such determination after a setback that every faculty was shortened and applied with double diligence. In this way, ultimate success could be achieved.”

Shortly after the Bay of Pigs, Kennedy began making sound decisions. He refused to commit American forces into a likely quagmire in Laos. He told Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, with convincing force, that the United States would stand firm in supporting West Berlin, and his commitment produced a standoff there with no need for military intervention. Speaking at the U.N., he toned down the hawkish rhetoric from his inauguration eight months before and said, “As we build an international capacity to keep peace, let us join in dismantling the national capacity to wage war. … I therefore propose that disarmament negotiations resume promptly and continue without interruption.”

These words and deeds by President Kennedy, in addition to his masterful handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis, were all instrumental to the first Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, ratified Oct. 10, 1963.

Though Kennedy increased the number of American “advisers” in Vietnam to 16,000 during his presidency, the consensus among historians is that it’s impossible to know whether he would have massively escalated U.S. involvement there as was done disastrously by his successor, Lyndon Johnson.

In summary, during JFK’s thousand-plus days in office, after a rocky start at the Bay of Pigs, his foreign policy transformed America, the Soviet Union and the world toward less hostility, more cooperation and recognition that a nuclear war would result in disaster for all.

Economic policy

Kennedy entered the White House amid a floundering economy. JFK biographer James N. Giglio noted that he began “with little background in economics and virtually no exposure to Keynesian economics.” Thus, despite the economy’s doldrums, Kennedy believed early on that the safest route forward was to make an Eisenhower-like commitment to a balanced budget and lower federal deficits.

When that approach kept things stagnated, JFK had what Sidey called an “economic metamorphosis.” He changed his position on Keynesian economics after listening to his Council of Economic Advisers and engaging in rigorous personal study. Yes, invoking Keynes would raise the deficit, though in Giglio’s analysis, Kennedy “grasped the logic of accepting temporarily larger deficits to achieve economic well-being.” In a December 1962 speech, he gave his rationale: “The lesson of the last decade is that budget deficits are not caused by wild-eyed spenders but by slow economic growth and periodic recessions. … The soundest way to raise revenues in the long run is to cut tax rates now.”

Though Kennedy did not succeed in getting his tax cut through Congress before his death, LBJ finished what JFK started. The Revenue Act of 1964 reduced the top tax rates on individuals and corporations, caused unemployment to drop, and increased the annual growth rate, while the inflation rate held at 1.3%.

Personal calm

JFK’s second trait that enhanced his presidency was his ability to stay calm in a crisis. The Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 almost triggered a nuclear war between the Soviet Union and the United States. As mentioned previously, JFK addressed it as he did because he had changed during the first 20 months of his presidency from an aggressive Cold Warrior into a leader who knew that a prudent foreign policy relied more on effective diplomacy than warfare.

When Kennedy learned of the Soviets having moved nuclear missiles into Cuba, he met with his advisers and identified options on how best to respond. Among them were an immediate air attack to bomb the missiles, an invasion of Cuba by American troops, and a Navy blockade to stop Soviet ships from sending more missiles. He knew that allowing missiles to stay in Cuba was not an option. Attorney General Robert Kennedy told his brother that to do nothing “would be an impeachable offense.” To add to the tension, action had to be taken quickly before the missile installation in Cuba was completed, and before commencing diplomatic overtures to Khrushchev that would likely stalemate.

JFK decided on the blockade option. Why? Pulitzer-winning historian Martin J. Sherwin’s answer: “It invited negotiation and avoided the certainty of Soviet bloodletting.”

The blockade caused Soviet ships bound for Cuba to turn around, which got urgent negotiations between Khrushchev and JFK to commence immediately thereafter.

Recognizing that Kennedy would never agree to allow the nukes to stay in Cuba, the Soviet leader proposed a trade of the withdrawal of his missiles from Cuba for the withdrawal of America’s missiles in Turkey. Sherwin: “Khrushchev knew he didn’t want war, and would negotiate his missiles out of Cuba. But he would make that trade only if he believed an American invasion of Cuba was imminent.” JFK communicated his intent to invade if the missiles weren’t removed.

From his analysis of the 42 hours of tapes made of JFK’s meetings during the 13-day crisis, Cold War historian Sheldon Stern determined that, “there were approximately a dozen times where Kennedy received — in my judgment — terrible, provocative, dangerous advice. In every case but one he rejected it.”

The crisis ended with the missiles-for-missiles trade and no nuclear war.

Kennedy biographer Mark Updegrove explained why JFK’s handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis became the defining event of his presidency: “His triumph owed to his restraint, dispassion and cool head. Khrushchev acknowledged them in his memoirs: ‘In the final analysis, Kennedy showed himself to be sober-minded and determined to avoid war. He didn’t let himself be frightened, nor did he become reckless. He didn’t overestimate America’s might, and he left himself a way out of the crisis.’ At that most perilous hour, his equanimity made all the difference.”

Rhetoric

JFK’s third key trait was his capacity to deliver words that spurred the nation to move forward guided by “the better angels of our nature,” to borrow the rhetoric of another great communicator.

Yes, the words used in his most important speeches came largely from speechwriter Ted Sorensen, though JFK sharply edited the drafts before he spoke to the nation. Sorensen knew what his boss wanted to say and then turned his thoughts into messages that resonated, reverberated and penetrated the soul of America.

In Kennedy’s inaugural address, he famously said, “My fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country.”

It didn’t take long for those words to inspire action. A month later, he signed an executive order that created the Peace Corps. Young people began volunteering and were sent to developing countries to teach English, construct homes and buildings and deliver food.

During its first year, the Peace Corps attracted 900 volunteers who served in 16 countries. Within five years, those numbers grew to 16,000 working in 52 countries.

Another example of Kennedy’s words inspiring progress came with his endorsement of America’s role in the space race, capped by his pledge to land a man on the moon by the end of the decade.

Four months into his presidency, Kennedy told Congress and the American people that winning the space race was a Cold War necessity: “If we are to win the battle that is now going on around the world between freedom and tyranny,” winning the space race “may hold the key to our future on Earth.”

After touring NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center, JFK gave a speech at Rice Stadium in Houston on Sept. 12, 1962, where he delivered these memorable words: “We choose to go to the moon in this decade not because it is easy, but because it is hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one we are willing to accept, unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win.”

Civil rights

In 1963, JFK again used his word power to move the nation forward on civil rights.

Until that summer, he took action on racial injustice only on a reactive basis. He dealt with the first two crises (violence toward Freedom Riders and racial integration at the University of Mississippi) from the perspective of doing what it took to restore order, not on the basis that confronting racism as the morally right thing to do.

In April 1963, events in Birmingham, Ala., moved Kennedy to make a major turn on civil rights. After Martin Luther King Jr. and hundreds protesters were arrested for their sit-ins at segregated lunch counters, Birmingham Commissioner of Public Safety Theophilus Eugene “Bull” Connor ordered his men to shoot firehoses and unleash attack dogs on African Americans of all ages.

As he watched the events in Birmingham unfold, JFK recognized that there would never be a national consensus on what should be done about civil rights, and a political solution was not going to happen. Shortly after that epiphany, Kennedy spoke to a national television audience.

“We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the Scriptures and as clear as the Constitution. … The heart of the question is whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities, whether we are going to treat our fellow Americans as we want to be treated. … It is time to act in Congress, in your state and local legislative body and, above all, in our daily lives. … A great change is at hand, and our task, our obligation, is to make that change peaceful and constructive for all.”

A few days later, he sent Congress a strong civil rights bill that covered equal access to public accommodations, school desegregation and employment discrimination. Although most members of Congress rejected it, they could not ignore the volcanic groundswell of support it had among large blocs of the American people.

Though JFK’s civil rights bill stayed bottled up in Congress for the last five months of his presidency, shortly after Kennedy’s death, Johnson pushed it into law on July 2, 1964. One of LBJ’s most formidable arguments: Passing it was the best tribute representatives and senators could make to honor their fallen leader’s legacy.

On Nov. 22, 2023, because “the dust has settled,” may we reflect on John F. Kennedy not by obsessing over conspiracy theories and personal indiscretions. Instead, may we appreciate the traits that caused his distinguished shortened presidency to peak just before he came to Dallas.